(program notes written for Note to Self: The Psychosexual films of Nazli Dinçel @ ERC 2/23/2016)

Lovemaking is not fluid. We start, stop, adjust, try too hard or not enough, let go, and enjoy. A certain mechanics is involved that can include both successes and failures. So too it is with moviemaking: roll, cut, and adjust for the right angle or shot. Rarely though is such disruption displayed for us as viewers, when sex is neatly packaged up in everything from Rom-Coms to Pornos. Even violence can seem fluid. Disruption, however, is a major theme in the film work of Nazli Dinçel, who takes to task representations of female sexuality through a highly personal artist’s cinema, with often only a crew of one, both behind and in front of the camera, and imbedded into the actual material surface of her medium of choice, 16mm film.

“She locks the bathroom door.” —Solitary Acts #4

For Solitary Acts #4, the filmmaker positioned the camera with remote shutter release and positioned her body to record as both camera operator and actor the so-called solitary act of masturbation. So-called because it is ultimately part of a public experience. About two-and-a-half minutes in and filling the frame with a warmly-lit vagina, hand sliding in and out, there is a question of what exactly is being recorded. The self, the body, pleasure? With the penis it’s just so much easier to recognize both arousal and the moment of orgasm. It’s obvious, visible, and potentially valuable. Writing about pornography in her book Hard Core: Power, Pleasure, and the “Frenzy of the Visible” Linda Williams notes, there is a “reliance on visible penile ejaculations (money shots) as proof of pleasure” (p. 8). Quelle photogénie! But these physiological responses aren’t quite as evident (or represented) when it comes to female genitalia. One must wonder how pleasure presents itself (and really in terms of images, presents itself for whom?).

Defined as relating to mental, emotional, and behavioral aspects of sexual development (Miriam-Webster Dictionary), psychosexual is a Freudian term, with psychosexual energy as the driving force behind one’s behavior as an adult, arrived at via five infamous childhood stages (i.e. oral, anal, etc.). While not an actual correlate, Dinçel’s Solitary Acts #4 and #5 chronologically reveal to the viewer certain moments in the sexual awakening of a young girl into her teen years. Of course, it isn’t the explicit imagery that is telling us, but rather those things that disrupt it. From what Freud taught, a disrupted stage leads to certain fixations later in life.

“She imagines kissing, sucking, kissing…” —Solitary Acts #5

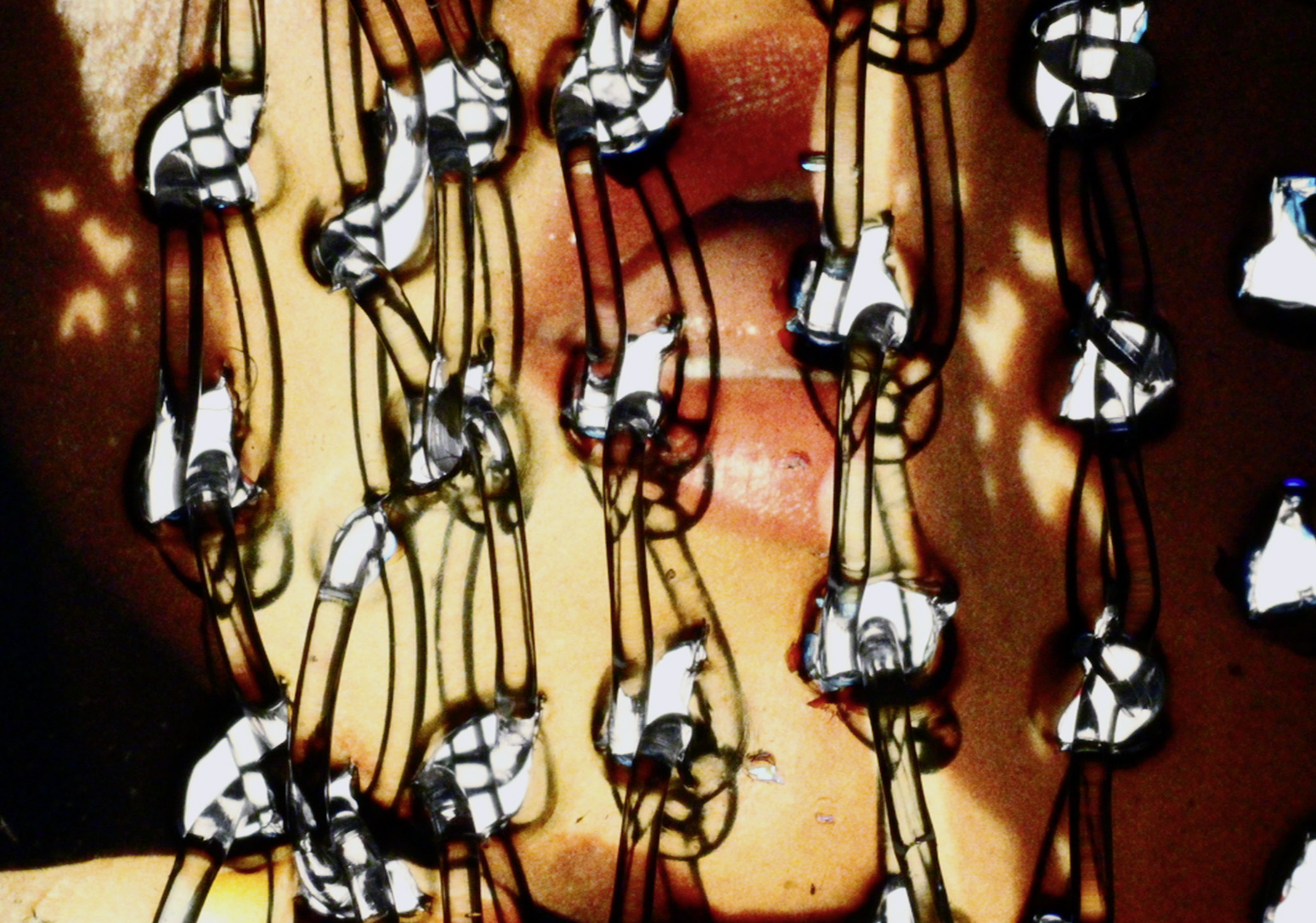

Confession seems too loaded a term, but it’s something like that, scratched onto the surface, frame-by-frame, of the film acetate, sometimes creating multiple columns within a single frame as in Her Silent Seaming or Solitary Acts #5; and to add tedium to envisioning such a tedious production task, let us not forget that just one second at a regular frame rate is composed of 24 frames. Even without fully understanding this aspect of production, the vibrating or typewritten words almost peeling off the surface demonstrate an intensity in her work as text/body and as therapeutic method. As Dinçel herself writes, “[o]ver-working the subject matter is a form of healing. The content is exhausted in the making of the films.” Light-leaks and other imperfections of hand-processing also intrude along with the cuts from the exacto knife, the punches from a sewing machine and typewriter, or the blows from a hammer that the film acetate receives. Manipulation of the film’s surface is more than a metaphor for the malleability of the body.

“He says it’s ok, I don’t like coming…” —Her Silent Seaming

Direct cuts to the optical track are also part of Dinçel’s production, disrupting the physical surface to effect the aural and visual experience. Recounting moments of intimacy in Her Silent Seaming, again via scratched text and in a mainly he said/he said address, over colorful and imperfect images of male genitalia and finally a symbolically eviscerated pomegranate, there is a pulsing pop that the filmmaker instructs should be played loud. But what we hear is not exactly when we see. Between the lens of the projector and the sound head there are 26 frames, meaning that what we hear is a past image. It’s impossible to catch up.

In her artist’s manifesto, Dinçel qualifies her interest in pornographic imagery, clarifying that her use of this imagery “is not primarily meant to arouse the viewer.” In addition to the complexity and intensity of the subject matter (far too much to unpack in these program notes), one shouldn’t ignore the beauty and humor of her work. The use of pop music, for example in Solitary Acts #4 with slow-mo Britney teasing “oops, I did it again,” is half making-fun at the filmmaker’s own relatable experiences of so-called bad sex. Making an appearance in all three of the Solitary Acts films, transforming as it is strung along, is that dang dangling carrot wrapped up in Freudian fixations to arrive as an unintentionally ironic metaphor. And at the center of the program “Note to Self” is the found film Sharing Orgasm: Communicating Your Sexual Response (1977) that is so earnest both in its original screenplay and in Dinçel’s placement of it as an attempt to mend past failures that its humor becomes highly palpable.

In terms of beauty, however, a stand out film might be Leafless (2011), which on its sensual surface seems like an update of Willard Maas’s Geography of the Body (1943), but now warmly-colored and somehow both fantastic and familiar, with cuts to real landscapes between the peaks and valleys of a lover’s body. Dinçel admits to never having seen the Maas film and while the body as landscape is hardly a novel concept, it is where her film is coming from that feels different.

Meant as a poem of textures, Leafless is a hand-processed film made by a young woman whose multi-located childhood between Turkey, the US, and Switzerland, appears in much of her work under the theme of dislocation. Although visually abstracting the body, the film has the sense of locating oneself by becoming familiar with a lover’s body as/via landscape. The sensual is found equally in the skin of a hand, the trunk of a tree, a penis, and shimmering reflections in the water. Is lovemaking fluid here? We can’t really know, but like Nazli Dinçel’s other films it feels honest, real, and tentative, accepting of its disruptions.

Mia Ferm

For the past five years Mia Ferm has been the co-director and co-programmer for the non-profit organization and screening series Cinema Project in Portland, Oregon. She is also currently the Education Programs Manager at the Northwest FIlm Center. In 2008 she received her MA in Cinema Studies from New York University and was a 2013 recipient of the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts Curatorial Fellowship